I Was Misled Into Leaving London for School in Ghana – But It Turned Out to Be a Life-Changing Decision

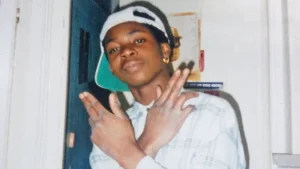

When my mother told me at 16 that we were going to Ghana for the summer holidays, I didn’t think twice. It seemed like a simple, short trip – nothing to worry about. Or so I thought.

One month in, everything changed. She dropped the bombshell: I wasn’t returning to London until I had “reformed” and earned enough GCSEs to continue my education.

I was deceived much like the British-Ghanaian teenager who recently took his parents to court in London for sending him to school in Ghana. In their defense, the parents argued they didn’t want their 14-year-old son to become “yet another black teenager stabbed to death in the streets of London.”

Back in the mid-1990s, my mother, a primary school teacher, had similar concerns.

I had been kicked out of two schools in the London Borough of Brent, associating with the wrong crowd – and becoming part of it. My closest friends ended up in prison for armed robbery, and had I stayed in London, I would have almost certainly joined them.

But being sent to Ghana felt like a punishment in its own right.

I can empathize, to some extent, with the teenager who said in his court statement that he felt like he was “living in hell.”

However, by the time I turned 21, I saw my mother’s decision for what it truly was – a blessing.

Unlike the boy at the heart of the court case, which he lost, I didn’t attend a boarding school in Ghana. Instead, my mother sent me to live with her two closest brothers. They wanted to keep a close eye on me, and they felt that being around other boarders might have distracted me even more.

I stayed with my Uncle Fiifi, a former UN environmentalist, in a town called Dansoman, just outside of Accra.

The lifestyle change was intense. In London, I had my own bedroom, access to washing machines, and the kind of independence I had recklessly abused.

In Ghana, my days began at 5:00 AM, when I would sweep the courtyard and wash my uncle’s often muddy pickup truck and my aunt’s car.

It was my aunt’s car that I would later steal – a moment that became a turning point in my life.

At the time, I didn’t even know how to drive properly. I treated a manual car like an automatic and ended up crashing it into a high-ranking soldier’s Mercedes.

I tried to run, but the soldier caught me and threatened to take me to Burma Camp, a notorious military base where people had disappeared without a trace in the past.

That encounter marked the last truly reckless thing I did.

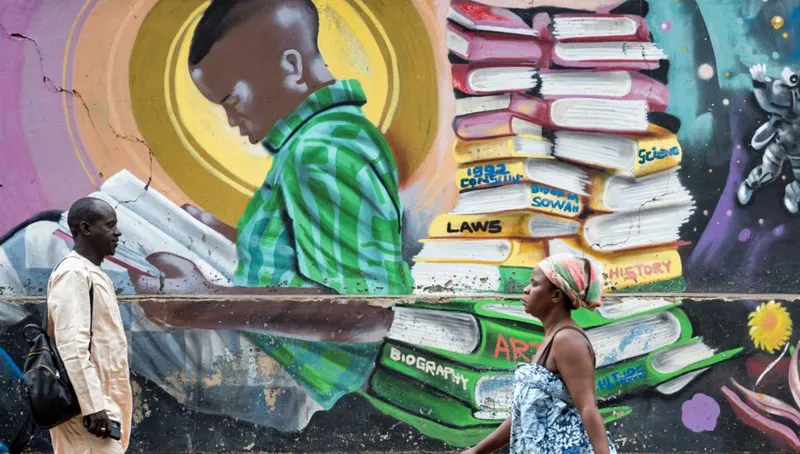

What I learned in Ghana wasn’t just discipline – it was perspective.

Living there made me realize how much I had taken for granted back in London.

Washing clothes by hand and helping my aunt prepare meals made me appreciate the effort that went into every task. In Ghana, food – like everything else – required patience. There were no microwaves or quick meals.

Making fufu, the traditional Ghanaian dish, for example, was a laborious task. It involved pounding boiled yams or cassava into a paste with a mortar. At the time, it felt like punishment, but looking back, I can see it was shaping my resilience.

My uncles initially considered sending me to prestigious schools like the Ghana International School or SOS-Hermann Gmeiner International College.

But they were wise. They knew I might just find new troublemakers and cause chaos. Instead, I was given private tuition at Accra Academy, a state secondary school that my late father had attended. It meant I often had one-on-one lessons or studied in small groups, allowing for a more tailored and focused education.

The lessons were in English, but outside of school, people around me often spoke in local languages. I found it easy to pick them up, probably because it was such an immersive experience.

Back in London, I used to love learning swear words in my mother’s Fante language, but I was far from fluent.

When I moved to Tema to live with my favorite uncle, Uncle Jojo – an agricultural expert – I continued my private tuition at Tema Secondary School.

Unlike the British teenager who recently claimed Ghana’s education system was substandard, I found it to be challenging and demanding.

Although I had been considered academically gifted back in the UK despite my rebellious behavior, I struggled in Ghana. My peers were far ahead in subjects like math and science. The rigor of the Ghanaian education system pushed me to study harder than I ever did back in London.

The result? I earned five GCSEs with grades C and above – an achievement I once thought was out of reach.

But beyond academics, Ghanaian society instilled values that have stayed with me for life.

Respect for elders was a fundamental part of everyday life. Wherever I lived, it was expected that you greet anyone older than you, whether you knew them or not.

Ghana didn’t just make me more disciplined and respectful – it made me fearless.

Football played a major role in this transformation. I played in parks with rough red clay surfaces, scattered with pebbles and stones. The goalposts were makeshift, made from wood and string. It was nothing like the well-kept pitches in England, but it toughened me in ways I never anticipated. No wonder so many of the best footballers in the English Premier League hail from West Africa.

Do you find 9jawave useful? Click here to give us five stars rating!